We all know that emotions significantly affect individuals’ behaviour. The stronger positive emotions aroused, the greater the chances that the behaviour can repeat itself in the future.

Emotions are an important driver to focus our attention, but that’s not all. Often emotions are the ones that push us to move, to act and, therefore, to make a decision.

If we think about emotions on a physiological level, we can say that our brain generates an alteration of activity in front of a certain stimulus – such as, for example, an advertising message. However, we are not always aware of this alteration because it is difficult to perceive. And it is even more difficult to tell it in words. Searching for information through questions therefore generates a search for a rational insight, about irrational processes.

Which chicken would you choose? Raghunathan and Huang’s experiment

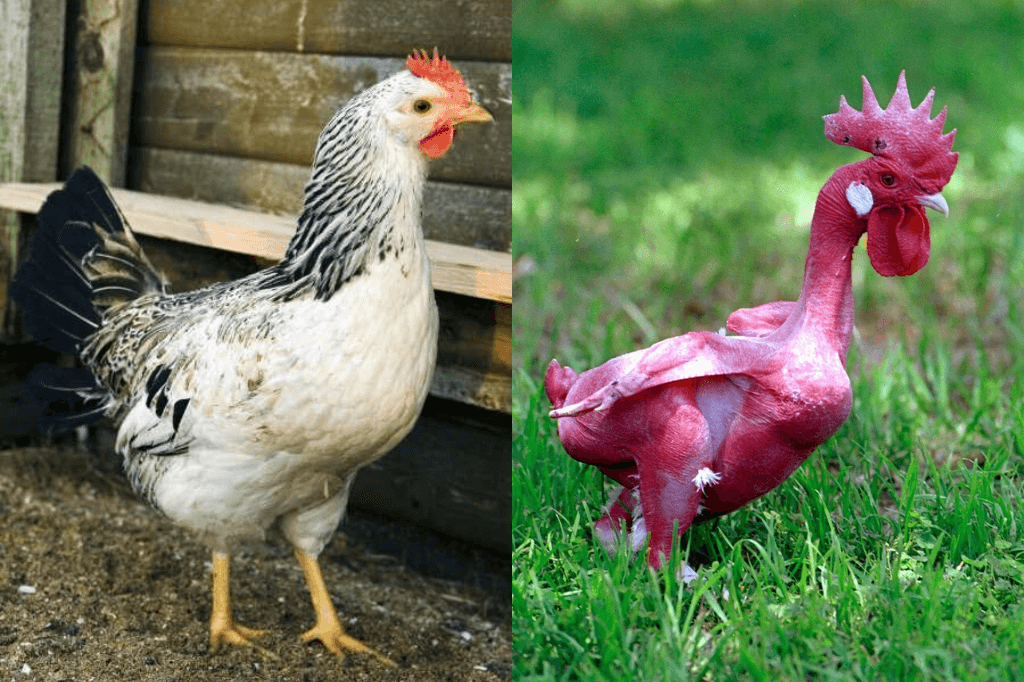

Many choices are therefore made because of unconscious motivations. To clarify the matter, I report the study conducted by Rai Raghunathan and Szu-Chi Huang. This is the test: look at the images below, which represent two very different chickens.

If I told you that white chicken is healthy, but less tasty, while pink chicken is tastier but less healthy, which of these two chickens would you choose to eat? And above all, why?

What if the information I provided about the two chickens was exactly the opposite? That is, the white chicken is less healthy but tasty and the pink one less tasty but healthy, would your choice change?

Most likely not. Or at least that’s what was shown in the study conducted by Raghunathan and Huang. The result was curious: the participants, regardless of the information, were all in agreement in systematically choosing the apparently healthier chicken. The only difference was related to the justification of the choice: no one tried to motivate their decision on the basis of the physical appearance of the animal and the emotion that the images aroused; everyone tried to respond rationally, excluding the emotional aspect.

In the first case, the justification was due to the fact that health was a more important factor than taste. In the second case, however, it was diametrically opposite.

But what really happened?

The phenomenon of post-hoc rationalization

The experiment I just told you is known in psychology as “post-hoc rationalization” and is a phenomenon present in all aspects of our daily lives. It occurs when in retrospect we try to justify a choice in a logical way, even if we are not fully aware of the mental processes that led us to that decision.

It happens for example when we are in the semi-deserted parking lot of a shopping centre and we have to choose where to leave the car. Why do we choose that parking space? To give an answer, you would probably start arguing and somehow convince yourself of that standpoint. But the rationalization of choice is a cognitive mechanism that occurs after the choice process. And for this reason, it doesn’t have much to do with it.

The real reasons that push us to the choice rarely coincide with the rationalization of the same. In our society it is considered unacceptable to make a decision based simply on instinctive factors. To avoid damaging the image we want to give of us, we resort to a plausible and socially acceptable motivation. This mechanism is so profound that we end up justifying not only with others, but also with ourselves. And in these cases it is a question of social desirability bias in the choice.

An example of bias: political elections and exit polls

In some contexts, the desire to join a social group or a decision perceived as prevalent, leads to denying not only the real reasons, but also the choice itself. A striking example is the socio-political context, particularly in cases of elections or referendums. It has happened more than once that exit polls were denied by the election results. The choice of the individual is not known and therefore there is no bias of social desirability, but with qualitative methods of investigation it is possible to know the reasons, once voted. The responses to these interviews are subject to bias and lead to a discrepancy between the investigation and the results of the vote.

The first historically relevant case was that of Tom Bradley. An African American candidate for the role of governor of California, Bradley lost the election despite all the exit polls, based on the interviews, identified him as a sure winner. But one must not go so far back in time to understand the effects of these investigations. Just think of the Trump elections and Brexit. In both cases the initial forecasts were far from final results.

For this reason, in similar contexts, simply interviewing people to know the drivers of choice is not always effective.

How can we overcome the social desirability bias?

The possibilities are many and mostly depend on the actual objectives of the test and the object of investigation. Undoubtedly we need to use tools that analyse unconscious processes, in order to evaluate the unconscious elements that lead people to make a decision. This is why neuroscience helps us find an answer.

Which is better, iPhone or Android?

On Google there are about 3,250,000,000 results when asked if iPhone or Android is better. And there are at least as many rational arguments and advice on the subject. But the moment you decided to buy a smartphone, you didn’t make this choice based on all these elements. You probably don’t even know most of these arguments. Try to give yourself a motivation now, before reading them. And then try reading the tips. You will see how they will tend to go in your head very well, but without you having them first think.

If you want to know more about how this type of test works, read this article in which we use it to study the brand perception of two other famous brands in comparison.